Are Visual or Mechanical Inspections Ever Truly 100%?

Metal inspection is a critical step in the manufacturing process, helping to ensure the quality of small metal parts that are the components of (literally) countless products. Yet, the concept of 100% inspection of parts is a somewhat tricky proposition.

That’s because, no matter what method of inspection you use, it is impossible for people to examine every tiny segment of a part’s surface — which means 100% inspection is not exactly 100%.

Whats, Hows, and Whens of Metal Inspection

Here at Metal Cutting, we typically do a sampling plan at the beginning of every project. In the plan, we spell out what dimensions of the parts we produce — their diameter, length, and so on — will be inspected, as well as how and when those inspections will occur.

As a rule, we use a c=0 sampling plan with an associated Acceptable Quality Level (AQL), which determines how many randomly selected parts in each lot will be inspected. Based on this plan, if just one randomly selected part fails inspection, then 100% inspection must be performed.

Metal inspection might occur in receiving, at a designated step (or steps) in the production process, at the end of the manufacturing (prior to packaging and delivery), or all of the above. In addition, an inspection might be requested as a result of a chance discovery.

For instance, when doing an inventory of incoming customer-supplied materials, such as long rods or tubes that will be cut off into small parts, we might notice and alert the customer to gouges, scratches, or other surface defects that could impact the end product. At that point, the customer would likely do one of three things:

- Ask to have the material returned to the supplier

- Give authorization for us to use the material as is

- Ask Metal Cutting to do a 100% visual inspection to eliminate defective materials

Since inspecting metal parts for quality is part of our DNA, we are always ready, willing, and able to meet such requests. However, the price of the job may need to be requoted if the customer-supplied material causes increased inspection time. In addition, we always remind customers that even 100% visual inspection cannot be 100% guaranteed.

To be sure, we are well-versed in and have an array of automated visual inspection machines with various capabilities that have very high accuracy, repeatability, and reliability. However, these machines are designed in advance for specific tasks.

Our automated inspection machines are not designed for the kinds of unintended visual defects that occur on metal parts and are caused by our vendors or our customer’s raw material vendors. In transactional terms, no one wants to pay us to have and use a machine to find something that should not be there in the first place.

Therefore, these added-on 100% visual inspections are done by human eyes.

Is Visual Metal Inspection 100%?

Visual inspection is commonly used to detect a variety of surface finish issues in metal parts, from corrosion and contamination to cracks and surface irregularities that can have an impact on product performance. This type of metal inspection ranges from examination with the naked eye to the use of sophisticated optical tools, such as high magnification microscopes.

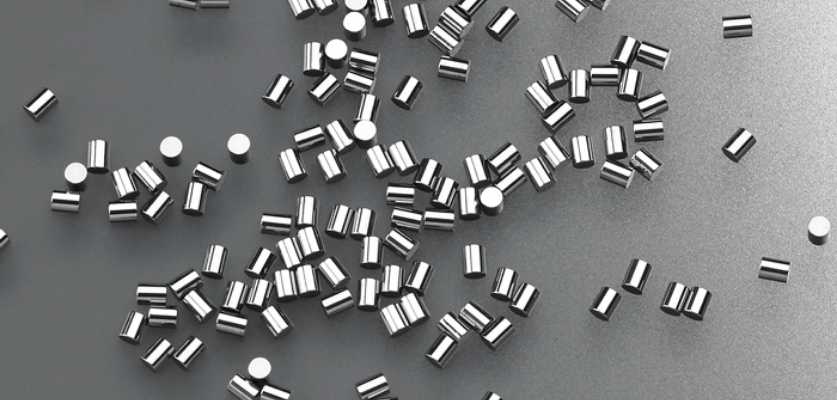

Performing 100% visual inspection generally involves looking at small parts at the closest possible level – for example, rolling small round rods or tubes under a microscope to examine every tiny section of the part’s surface.

That requires a human being to physically move the part while ensuring that the surface is being examined at all 360º of the tube or rod’s circumference along 100% of the part’s length. Blink, and a minuscule but important flaw can easily be missed.

What’s more, visual inspectors, utilizing their experience, decide if a part passes or fails by judging a defect’s relative size, coloration, depth, and other traits, making the results subjective. In addition, human beings are flawed and even the most diligent inspector can make mistakes.

In fact, human error is a normal part of any process where people are involved, and especially where tasks are high volume and highly repetitive. Among a vast array of productivity studies and data, the consensus is that for high-volume activities, human beings can often show accuracy rates of 80% to 90%, with a steep fall off in accuracy after a certain volume of repetitions.

A human handler might misread a micrometer, put parts in the wrong bin, or simply “blink” at a crucial millisecond. Even where you have a binary, pass-fail method of inspection, judgment and human error will have an impact on the results of a 100% visual inspection.

It’s not that any particular person is incapable of 100% accuracy in a particular task. But unlike a mechanized or computationally executed task, a human being finds it very difficult to be perfect. After all, to err is human!

Is Mechanical Metal Inspection 100%?

Of course, metal inspection is not limited to visual inspection “by eye” or using optical tools; many manufacturers (including Metal Cutting, as noted above) also utilize various machines that can automate much of the parts inspection process.

It is possible to purchase a piece of equipment that would inspect 100% of parts perfectly for dimensions and some color characteristics. But whenever there is a need for judgment or no standard for pass-fail, mechanical inspection (like visual inspection) cannot be 100% guaranteed.

For instance, eddy current testing (ECT) utilizes electromagnetic induction to inspect metal parts for surface flaws such as cracks, pitting, and corrosion. It is also used to measure the thickness of parts such as thin-walled tubing.

However, because ECT is based on indirect measurement, the correlation between instrument readings and the structural characteristics of the parts being inspected will vary and must be carefully established according to the specific application. (Read more about eddy current testing.)

The human factor in mechanical inspection

There is also a human factor in the mechanical inspection of metal parts, creating room for human error in vital steps such as programming the machines and setting the lighting for tools like vision measuring systems. Human beings literally have a hand in tasks such as feeding parts into machines and applying pressure when using micrometers and other measuring equipment.